Perhaps you are new to the children’s book genre (if so, welcome!), or you need to read with someone else’s kid or to a class, you might suddenly find yourself wondering if you’ve been reading them right. Or perhaps you feel as though you and your child aren’t connecting over the books you are reading together and want to build that time up (props for searching for an answer), or maybe you love children’s literature and just want to be more effective when you read it (One of us! One of us!). In any case, ask yourself these questions while you read a picture book to a child to encourage more learning and create a better reading experience:

- Am I pointing to the words as we read?

- Am I helping my child develop motor skills?

- How am I helping develop vocabulary and reading comprehension?

These questions can apply to just about every book you read with your child and taking the time to think about these before reading a book can add an extra dimension of fun and education to the experience of reading a book together. So, think about incorporating one or more of these questions into your reading time and see if it makes a difference in the quality of the time you spend with your kid and what they take from the experience.

*This post may contain Amazon or other affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Am I pointing to the words as we read?

When you read a story, underline the words you read as you go. Your adult brain knows that those squiggles on the page are what is telling you the story, not the pictures, but your child may not understand that yet, which is okay! By pointing to the words as you read them you are encouraging print awareness, one of the early literacy skills you can read about in the post Building Reading Skills at Home.

This simple action, repeated over time will reinforce the idea that those shapes are the ones telling the story, so they must be important. If it is important then your child will be more interested in figuring out what this means.

Read the emphasis the text places on the words. If one word is larger or more stretched out, read it that way. As an adult, you read and understand the punctuation in a novel, it adds meaning to the words. Creative text in children’s literature is their version of punctuation. They haven’t learned all the fine points of grammar yet, but they understand when the word is big and red it has a different meaning than normal print. Tracking the words and reading them the way they are printed teaches your child that the way the word is written informs some of the meaning as well.

Ernest the Moose Who Doesn’t Fit by Catherine Rayner and Open Very Carefully: A Book with Bite by Nick Bromley, are two good examples of books with varied text that you can interact with while you read. Change your speed and pitch when you get to words with different text to reinforce the meaning, and just make the reading more fun all around.

Am I helping my child develop motor skills?

Motor skills can be developed even while reading a book. If they are able, let your child hold the book to strengthen the muscles in their arms and torso and turn the pages with their hands to strengthen the smaller muscles in hands and wrists. Part of learning to read is learning how to turn the pages of a book Letting them get the feel for holding a book and simultaneously turning the pages will develop hand-eye coordination and muscle strength. If they can’t quite manage both yet just let your child turn the pages. It is okay if they don’t do it right at first, this is all part of the learning experience.

Some kids just have the wiggles. You may know this about your child, or you may discover this after trying to sit them down to read. There is no need to fight it, you can harness the power of the wiggles to make reading more fun! Choose a book that has a movement that the two of you can do together.

Try Who Has Wiggle Waggle Toes by Vicky Shiefman, stand while you read and both you and your little one can wiggle-waggle as you go, or do a little dance with Spunky Little Monkey by Bill Martin Jr and Michael Sampson.

If you’re after a book you can read sitting down but need to keep your child more engaged, try Herve Tullet’s Press Here or Don’t Push the Button by Bill Cotter.

They will keep your child interested and cracking up the whole way through, especially if you really play into the drama of the story. A hidden benefit to adding an action to a story is reinforcing the meaning of the word. If the character gasped in surprise, act out a gasp and have your child do it too.

Jan Thomas creates expressive characters that give you space to talk about expressions with your child. Make funny faces at each other with Can You Make a Scary Face and talk about the facial expressions of the characters, and how they might feel, in Is Everyone Ready for Fun?

Stories that do not specifically encourage movement can still be adapted to a wiggler. Many picture books use rhymes or repetition in some form. Invent your own special movement that will happen whenever a certain phrase is said, add a clap or a jump to sync up to a repeated rhyme. Not only will the extra burst of energy your child used up help you out later, turning the reading into an experience will help them learn better and be a special moment of bonding for you. Got more wiggles to work out? In the post Read the Wiggles Out we go more in depth about reading to a child with lots of energy and give you specific ways to accomplish it.

How am I helping develop vocabulary and reading comprehension?

Children who are read to more often have an increased vocabulary because they are exposed to more infrequently used words than children who are simply spoken to. In 2019 the “Million Word Gap” study was revamped and tested again. It still found that kindergarten aged kids whose caregivers read them five or more books a day had heard 1.4 million more words than children whose caregivers did not read to them, and had only heard 4,662 word five years old (Ohio State University, 2019).

That is a huge difference when it comes to learning to read, more word exposure means an easier time reading. The drastic difference in number of words heard is because the words used in books tend to be very different from the ones we use in conversation. They are often more complex, with more syllables and have concepts that may not normally be talked about at home, such as science or abstract concepts. There are easy ways to build vocabulary and comprehension right into reading the book.

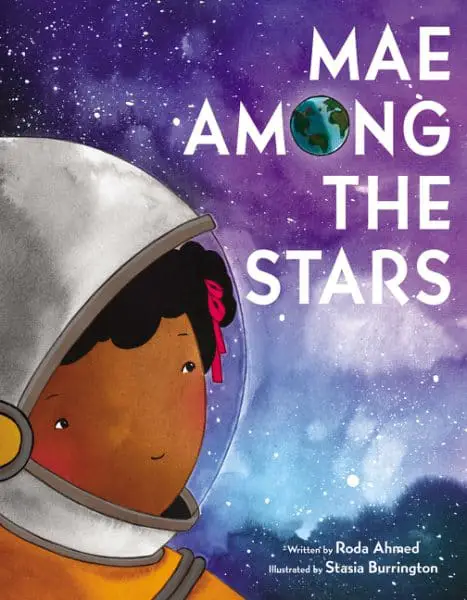

Start with the book cover. What kinds of things are on the cover? Are there any new things? For example, in Mae Among the Stars, Mae is wearing an astronaut’s helmet and space suit, talk about what she is wearing and what other things she might need to go into space. If your child is very young, what colors do you see?

How was the cover illustrated? What do you think all these things might tell us about the story? When you start your story, tell them who the author is, ask if they know what an ‘author’ does. If not, explain that the author writes the story. Every time you start a new book ask the question and after a few times, they will excitedly exclaim that “the author writes the story!” When your child has that one down, work on what the illustrator does.

As you read, when you come across an unfamiliar word take the time to explain what it means and use it in an example your child will understand, don’t worry about pausing while you read. If you aren’t sure what a word means, that is okay too! Show your child how to look up a word either in a real dictionary or in a dictionary app.

Read Mae Among the Stars by Roda Ahmed for scientific words or The Word Collector by Peter H. Reynolds pure vocabulary fun and take time to talk about what the words mean. You don’t have to define every word, but make sure your child is understanding what you are reading. The next time you read the book, you can tackle different words.

Taking the time to read a few books a day will make a huge difference in your child’s ability to learn to read, even if the only thing that happens is reading a couple of stories at bedtime.

Many children’s books feature a word or phrase of repetition, focus on that the first few times you read that story. Make sure your child knows what it means. Read the book again later and ask if they remember what it means, gently remind them if they don’t. Repeat until they understand and remember it, then choose a new word to focus on.

*This is, of course, a general guide and is not meant to diagnose. If you have concerns about your child’s behavior or development please be sure to speak with a medical professional, your child’s physician or teacher.